I have read Florida’s State Academic Standards – Social Studies, 2023, specifically, the “strand” for African American History. (In the Standards, a strand and its sub-strands detail the subject matter that is to be taught to students.) These have been the subject of some controversy.

I have some issues with the standards, but not about the now hot-button topic of the “benefit” of skilled craftsmanship for enslaved people. My concerns center on race and the use of the Declaration of Independence in defining the concepts of liberty, equality, and rights. I amlorida, not an educator or historian, but I do think this will be of interest.

***

First, a word from our founders. This is from the iconic Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

The Declaration was referenced by then US Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi in his Farewell Address to the Senate on January 21, 1861. Davis explained why his state was leaving the Union to join what would become the Confederate States of America:

It… {is the} belief that {under the Lincoln administration} we are to be deprived… of the rights which our fathers bequeathed to us, which has brought Mississippi into her present decision {to secede from the Union}.

She has heard proclaimed the theory that all men are created free and equal, and this made the basis of an attack upon her social institutions; and the sacred Declaration of Independence has been invoked to maintain the position of the equality of the races.

{We believe} That Declaration of Independence is to be construed by the circumstances and purposes for which it was made…They have no reference to the slave; else, how happened it that among the items of arraignment made against George III was that he endeavored to do just what the North has been endeavoring of late to do–to stir up insurrection among our slaves?

Had the Declaration announced that the negroes were free and equal, how was the Prince to be arraigned for stirring up insurrection among them? And how was this to be enumerated among the high crimes which caused the colonies to sever their connection with the mother country?

When our Constitution was formed… we find provision made for that very class of persons as property; they {Negroes} were not put upon the footing of equality with white men–not even upon that of paupers and convicts; but, so far as representation was concerned, were discriminated against as a lower caste, only to be represented in the numerical proportion of three fifths.

Jefferson Davis – who became the President of the Confederacy – believed that the Declaration of Independence was a sacred document. The claims of contemporaries like Abraham Lincoln and others – that the Declaration included the Negro when saying all men were created equal – must have seemed like blasphemy to him.

At the least, Davis believed that Lincoln and others misunderstood the meaning of the Declaration, the intentions of the founders, and the social structures of the founders’ times. The founders did not put Negroes on equal footing with white men, thought Davis. Heck, they didn’t even make Negroes equal to (white) paupers or convicts!

The key point to understand is that the racial applicability of liberty, equality and inalienable rights was contested prior to the Civil War. Make no mistake, many Europeans/whites did believe that Africans were included in the family of “all men.” And that informed the abolition of slavery in the Northern or “free” states. But Southerners in general, and many Northerners, strongly disagreed with that.

This slavery-affirming viewpoint was codified and canonized in the famous Dred Scott decision of 1857. In a case concerning the institution of slavery, the Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling which stated:

In the opinion of the court, the legislation and histories of the times, and the language used in the Declaration of Independence, show, that neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument.

It is difficult at this day to realize the state of public opinion in relation to that unfortunate race, which prevailed in the civilized and enlightened portions of the world at the time of the Declaration of Independence, and when the Constitution of the United States was framed and adopted. But the public history of every European nation displays it in a manner too plain to be mistaken.

They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold, and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic, whenever a profit could be made by it.

This opinion was at that time fixed and universal in the civilized portion of the white race… And in no nation was this opinion firmly fixed or more uniformly acted upon than by the English Government and English people. They not only seized them on the coast of Africa, and sold them or held them in slavery for their own use; but they took them as ordinary articles of merchandise to every country where they could make a profit on them, and were far more extensively engaged in this commerce, than any other nation in the world.”

This idea that Africans were “beings of an inferior order… so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect” – which we today call white supremacy – was not an outlier. It was not considered aberrant or “wrong.” It was endemic. And by virtue of that Supreme Court ruling, it was literally the law of the land.

Against this backdrop of historical fact, what do we make of the Florida standards concerning African American history?

***

Here’s one of my problems with the Florida standards: they don’t address the fact that the Declaration’s notions of liberty, equality, and rights were contested and controversial when it came to issues of race.

So, for example: one of the sub-strands, numbered “SS.912.AA.2.7,” instructs: “Analyze the contributions of founding principles of liberty, justice and equality in the quest to end slavery.” This wording seems to presume that the “founding principles” of the United States were such that they could only contribute to “the quest to end slavery.” Or that principles unrelated to liberty, equality, and rights (such as racial supremacy) are not important in studying the black experience. Those presumptions are false, as the words of the 1856 Supreme Court and Jefferson Davis would indicate, and the lived experience of enslaved people would illustrate.

The Standards should say: “Analyze how different interpretations of the founding principles of liberty, justice and equality either supported slavery, or, served to end it.” This would lead to a more complete, balanced, and correct review and understanding of how Europeans in the United States practically applied the aspirational values of the founders.

If the Standards’ writers are in fact trying to create the impression that the founding principles could only be, or must only be, interpreted as anti-slavery, then they are being deliberately ahistorical.

Or take the example of SS.912.AA.2.10: Evaluate the Abolitionist Movement and its leaders and how they contributed in different ways to eliminate slavery. That’s a fair route of inquiry. But there is no corresponding call for the evaluation of the “Slavery as a Positive Good” argument and other rationales for maintaining slavery. What we have here is the yin without them yang… incompleteness.

To be sure, I am all for the study of anti-slavery, Abolitionism, anti-racism, and the like. But history is not about picking favorites. Emphasizing these ideas, and not the intellectual, emotional, and cultural underpinnings of pro-slavery, can only lead to the incomplete and incorrect understanding of how slavery endured and thrived. Pro-slavery views directly impacted the black experience, arguably much more so than anti-slavery and other related beliefs (90% of African Americans were enslaved when the Civil War began). Emphasizing one set of views, and not the others, is bad history.

***

Why is this happening? I don’t know, but I can speculate. In the political (conservative) climate that green-housed these standards, acknowledging white supremacist ideology among the founders is politically incorrect. It smacks of Project 1619. And it does not escape me that this strand never uses the term “white supremacy,” and uses the term “racism” just once, when talking about Reconstruction… it’s as if those were dirty words.

Additionally, the writers might be fearful of any class instruction that would make some students embarrassed, uncomfortable or guilty. Acknowledging white supremacy might do that, if only unintentionally.

So, they adopted the strategy of ignoring or deemphasizing certain aspects of our history, while emphasizing others that make for a positive spin. Basically, they are whitewashing history by the way they teach it.

They claim this is objective history, but it’s not. What we have is an approach to history that makes supremacist views almost ephemeral by refusing to focus on them. Meanwhile presentist views about what liberty, equality and rights meant in the past are made to seem practically pre-destined and inevitable. Not a good look, Florida.

***

I would add one more point, which I know is controversial. In historical instruction, there is this idea that the facts should be objectively stated. And I agree with that.

But it’s not enough. Notions of racial supremacy did exist and do exist, and it’s not enough to make the objective statement that they existed. Otherwise, students who hear of these things will not know if they are right or wrong. And if they don’t hear that these notions are wrong, they might think it’s OK to have those views themselves. I think that in the case of the institution of slavery, condemnation is appropriate. Such condemnation should not be avoided for fear of being “subjective.”

The writers of the Standards are trying to avoid being, let’s use the word, judgmental. They don’t want to say that the founders had views which were “bad.” What they do, or posit, or simply imply, is that the “founding principles,” for example, led to the “quest to end slavery.” (Even as they did not lead to the end of slavery itself.) Such references to the principles makes us “feel” good about them, even if the instruction does not subjectively state that they are good.

With this, they can avoid having to say that racial supremacy was subjectively bad. The framing is that the founding principles were inherently anti-slavery and pro-racial equality (which is not true); and that slavery was counter to those values. (Jeff Davis and the 1857 Supreme Court, among many others, would not agree). The expected outcome is the conclusion or feeling among students that founding principles were good for Americans in general and even African Americans, even though the vast majority of black folks remained in captivity.

To repeat an earlier point: many African Americans did in fact benefit those principles. Specifically, they benefitted in the North, where slavery was abolished before the Civil War. But those principles, whatever their actual nature or practical (not aspirational) value, did not end slavery in the South; and as mentioned earlier, 90% of African Americans were enslaved when the Civil War began. Meanwhile, the end of slavery was contingent on the United States’ victory in their war to preserve the Union.

These instructional/pedagogical gymnastics would not be necessary if standards writers could just (a) admit that racial supremacist belief was a cornerstone (certainly not the only one) of the early portion of the American experiment; (b) acknowledge that those beliefs are counter to the values we have today.

But many people simply refuse to do that. They want to believe and say that America was right from the start, possessed of purity of value, possessed of values that mirror those we have today. The fact is, many of our current values were not present at the nation’s founding. They are the culmination of values that have evolved over time and will continue to evolve. And as Americans have evolved, in large part, they have progressed.

I close by noting that when citing founding principles, the Standards fail to note the founding principle of revolution against injustice. The pushback against injustice did not stop in the 18th century, but has become a part of our nature. Our present day understanding of equality, liberty, inalienable rights, and justice exist because of the progress we have made in becoming a better people, in crafting a more perfect Union. That’s a lesson worth teaching.

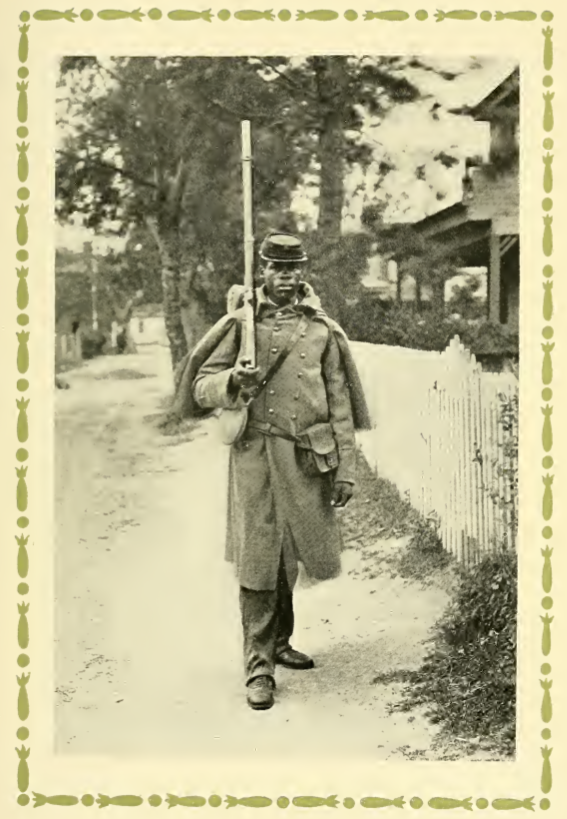

Image Description: “August 28, 1949 – Joseph Clovese, G.A.R. Veteran, 105 Years Old At The 83rd And Final G.A.R. Encampment In Indianapolis, Indiana.”

Image Description: “August 28, 1949 – Joseph Clovese, G.A.R. Veteran, 105 Years Old At The 83rd And Final G.A.R. Encampment In Indianapolis, Indiana.”