Henry McNeal Turner, writer, editor, army chaplain, religious leader, and political leader in the second half of the 19th century.

Source: African Letters by Bishop H M Turner, 1983; picture is from the Electronic Version of the book at the DocSouth site of the University of North Carolina.

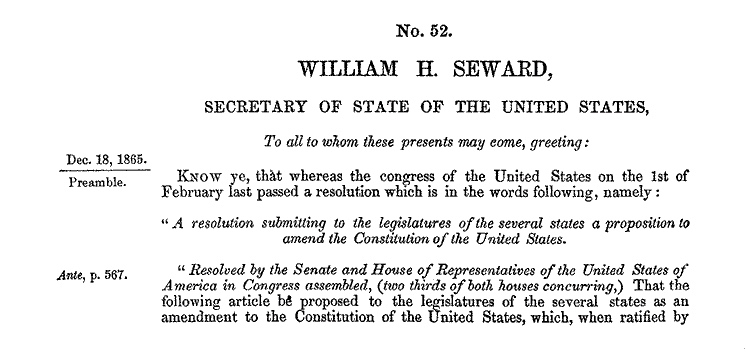

Henry McNeal Turner (1834-1915) was one of the most important African Americans of the 19th century. Born free in South Carolina, he was a leader in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, served as a United States army chaplain during the Civil War, was a Georgia state legislator during the Reconstruction era, and was also a writer and editor.

In the January 1913 issue of the A. M. E. Church Review, Turner wrote about his memory of the release of the Emancipation Proclamation by Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863. “We are now upon the verge of the fiftieth anniversary, since the Immortal Abraham Lincoln, then President of the United States, by the grace of God hurled against the institution of American slavery the thunderbolt which had been smelted in the furnace of fair play, justice and eternal equity,” he wrote. “Well do I remember the circumstances and incidents connected with my surroundings and experience on that occasion.”

He continued with poignant and pointed memories of that “thunderbolt,” which offer us a view into how African Americans, and many white Americans, felt on that momentous occasion:

In 1862, on the 22d day of September, Mr. Lincoln issued a proclamation (the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation) that in a hundred days, unless the rebel army disbanded, and the several Southern states resumed their relation to the general government, he would declare the slaves in all the states free with a few local exceptions. The newspapers of the country were prolific and unsparing in their laudations of Mr. Lincoln. Every orator after reviewing in their richest eloquence, concluded their speeches and orations by saying, “God save Abraham Lincoln,” or “God bless our President.” Mass-meetings were held in Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, Boston, Cincinnati, Cleveland, St. Louis, San Francisco and hundreds of minor towns, and such a time I never expect to witness on earth in the future. I may witness such a time again in heaven, but not in the flesh.

In the great Union Cooper Hall in New York City, a colored man leaped and jumped with so much agility when the proclamation was read that he drew the attention of every man and woman, till Mr. Lincoln’s proclamation was scarcely listened to. New songs were sung and new poems were composed, and the people shouted to such an extent that horses became frightened, and many ran away and smashed carriages into kindling wood. Whites and blacks realized no racial discriminations.

On the first day of January, 1863, odd and unique conditions attended every mass-meeting, and the papers of the following day were not able to give them in anything like detail. Long before sunset Israel Church and its yard were crowded with people. The writer was vociferously cheered in every direction he went because in a sermon I tried to deliver I had said that Richmond, the headquarters of the Southern Confederacy, would never fall till black men led the army against this great slave-mart, nor did it fall and succumb to the general government till black men went in first. This was only a popular prediction, and delivered under a general excitement, but strange to say, it was fully realized.

Seeing such a multitude of people in and around my church, I hurriedly went up to the office of the first paper in which the proclamation of freedom (the final version of the Emancipation Proclamation) could be printed, known as the “Evening Star,” and squeezed myself through the dense crowd that was waiting for the paper. The first sheet run off with the proclamation in it was grabbed for by three of us, but some active young man got possession of it and fled. The next sheet was grabbed for by several, and was torn into tatters. The third sheet from the press was grabbed for by several, but I succeeded in procuring so much of it as contained the proclamation, and off I went for life and death.

Down Pennsylvania Avenue (in Washington, DC) I ran as for my life, and when the people saw me coming with the paper in my hand they raised a shouting cheer that was almost deafening. As many as could get around me lifted me to a great platform, and I started to read the proclamation. I had run the best end of a mile, I was out of breath, and could not read. Mr. Hinton, to whom I handed the paper, read it with great force and clearness. While he was reading every kind of demonstration and gesticulation was going on. Men squealed, women fainted, dogs barked, white and colored people shook hands, songs were sung, and by this time cannons began to fire at the navy-yard, and follow in the wake of the roar that had for some time been going on behind the White House. Every face had a smile, and even the dumb animals seemed to realize that some extraordinary event had taken place.

Great processions of colored and white men marched to and fro and passed in front of the White House and congratulated President Lincoln on his proclamation. The President came to the window and made responsive bows, and thousands told him, if he would come out of that palace, they would hug him to death. Mr. Lincoln, however, kept at a safe distance from the multitude, who were frenzied to distraction over his proclamation.

I do not know the extent that the excitement in Russia led to, when the humane Emperor proclaimed the freedom of twenty-two million serfs, I think in 1862, but the jubilation that attended the proclamation of freedom by His Excellency Abraham Lincoln, I am sure has never been surpassed, if it has ever been equaled. Nor do I believe it will ever be duplicated again.

Rumor said that in several instances the very thought of being set at liberty and having no more auction blocks, no more Negro-traders, no more forced parting of man and wife, no more separation of parents and children, no more horrors of slavery, was so elative and heart gladdening that scores of colored people literally fell dead with joy. It was indeed a time of times, and a half time, nothing like it will ever be seen again in this life. Our entrance into Heaven itself will only form a counterpart. January 1st, 1913, will be fifty years since Mr. Lincoln’s proclamation stirred the world and avalanched America with joy, and the first day of next January, 1913, our race should fill every Church, every hall, and every preacher regardless of denomination should deliver a speech on the results of the proclamation.

No doubt, many of his fellow church people read this and exclaimed, “Amen, my brother, Amen.”

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/www.loc.gov/exhibits/odyssey/archive/04/0404001r.jpg)

![Negro quarters on Fripp Place, St. Helena Is. [i.e. Island], S.C. 2a](https://jubiloemancipationcentury.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/negro-quarters-on-fripp-place-st-helena-is-i-e-island-s-c-2a.png?w=869)