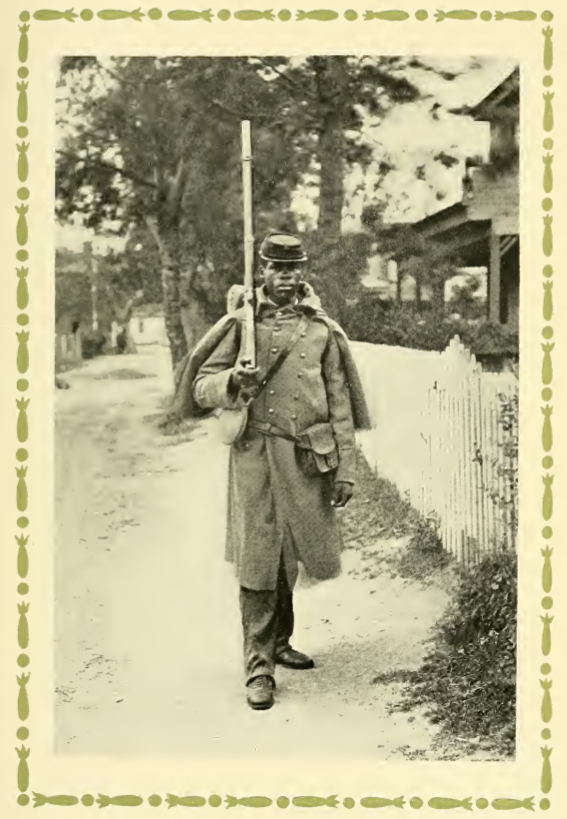

African American Union Soldier with Pistol, circa Civil War era (1860s). It was very common for Civil War soldiers to take pictures with their firearms, or props of firearms.

Image Source: Library of Congress; Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsca-11298; see more information about the photo here.

****

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

– Second Amendment to the US Constitution

“The great object is, that every man be armed. […] Every one who is able may have a gun.”

– Patrick Henry

“[if negroes were] entitled to the privileges and immunities of [white] citizens, …it would give persons of the Negro race… the right… to keep and bear arms wherever they want… inevitably producing discontent and insubordination among them, and endangering the peace and safety of the state…”

– Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney, in the 1857 Dred Scott decision

“Remember that the musket – the United States musket with its bayonet of steel – is better than all mere parchment guarantees of liberty. In your hands that musket means liberty; and should your constitutional rights at the close of this war be denied, which in the nature of things, it cannot be, your brethren are safe while you have a Constitution which proclaims your right to keep and bear arms.”

– Frederick Douglass, in an 1863 recruitment speech imploring black to join the Union army during the Civil War

****

[This is a re-blog of a post that I published in 2012.]

The current debate about gun control, spurred by incidents such as the Newtown Tragedy of December, 2012, and more recent shootings that can be found via Internet search (such as here), gives me pause me to reflect on the history of firearms access for African Americans. This history does not paint a pretty picture, but it adds a new perspective on our discussion of the right to bear arms.

A review of the history indicates that for over two centuries, the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the national, state, and local governments have been engaged in a project to limit African Americans’ access to guns. This project was not conducted in secret; the people involved made it unequivocally clear that they did not want people of African descent to have firearms. Blacks with guns were seen as a threat to the safety, politics, and domination of the white majority, and the law was used to remove that threat. For African Americans, “gun control” has almost always been synonymous with “keep African Americans from getting guns.”

To be clear: I am not taking any position regarding gun access policy. I hope that no one who reads this piece will assume that I am advocating a particular viewpoint concerning gun rights and gun control issues.

What I do want to do, is provide an abridged and slightly selective timeline of African Americans’ experience with bearing arms. There is so much to this story, it’s impossible to contain it all within one blog post – and this post is somewhat lengthy as it is. But for those who are not familiar with the subject, this will be informative and useful.

There is a sadly ironic, perhaps tragic aspect to this history. Guns have become the scourge of the urban landscape. So-called “black on black” crime has become endemic in certain communities, and guns are an unfortunate aspect of this. During the slavery, Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras, laws left blacks relatively defenseless against a tide of racial terrorism; African Americans were outmanned and outgunned. But now many black communities are awash in guns, and instead of firearms being used for self-defense, they are being used for self-destruction. Sometimes the arc of history bends in the wrong direction.

For more information on this subject, two good “starter” pieces on this topic are here and here. Two useful books on the subject is Freedmen, the Fourteenth Amendment, and the Right to Bear Arms, 1866-1876 by Stephen P. Halbrook, and Negroes and the Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms, by Nicholas Johnson. But there are many other journal articles, books, and other references that are available via Internet search for those who want to really get in depth on this subject.

I will begin at the middle of the 18th century, and go forward to the 21st century.

****

1779 During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress – which represents American colonists seeking independence from Britain – offers slave masters in South Carolina and Georgia $1,000 for each slave they provide to the Continental army. However, the legislatures of both states refused the offer. Apparently, the risk of arming slaves, who might want or demand freedom in exchange for their service, is more threatening than the British Army.

1792 Congress passes the Militia Acts, which limit service in militias to free white males. This restriction is prompted in part by fears that, as in the case of the Haitian slave revolt, free blacks will unite with slaves and use their guns and military training to mount an armed insurrection against slaveholders. The measures are interpreted as meaning that blacks cannot join the United States army.

1811 Hundreds of slaves, armed with guns, knives, and axes, become part of the largest slave rebellion on American soil, in New Orleans, Louisiana. The importance of taking arms is noted in the book American Uprising: American Uprising: The Untold Story of America’s Largest Slave Revolt by Daniel Rasmussen,

Baptized with the blood of his former master, Charles (the leader of the slave rebellion) and his men broke into the stores in the basement (of his master’s) mansion, taking muskets and militia uniforms, stockpiled in case of domestic insurrection. Many of the slaves had learned to shoot muskets in African civil wars, while others would fight mor effectively with tha cane knives and axes they wielded in the hot Louisiana sun. As his men gathered weapons and shoved ammunition in bags, Charles and several of his fellow slaves cast off the distinctive cheap cotton slave clothes and put on the (master’s) uniforms.

Unfortunately for the slaves, their revolt was beaten back by the superior force of local authorities, and they suffered a horrible punishment after the smoke cleared.

1831 Nat Turner leads a slave rebellion in Southampton County, Virginia. The rebels kill over 50 white people, the highest number of fatalities caused by slave uprisings in the South. The rebellion was put down within a few days, but Turner survived in hiding for over two months.

After the rebellion, legislatures in the slave states passed new laws prohibiting the education of slaves and free blacks, restricting rights of assembly and other civil rights for free blacks, and requiring white ministers to be present at black worship services.

1831 Three states – Florida, Maryland and Virginia – enact laws which ban black ownership of guns.

Continue reading →

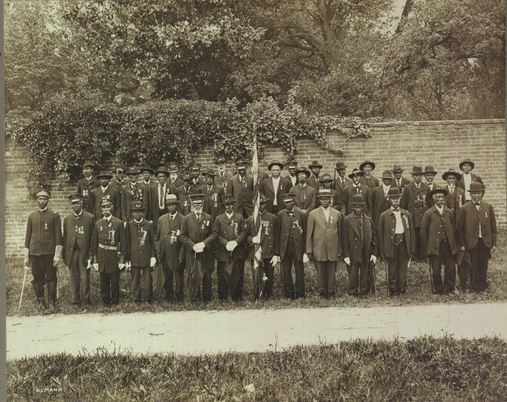

Image Description: “August 28, 1949 – Joseph Clovese, G.A.R. Veteran, 105 Years Old At The 83rd And Final G.A.R. Encampment In Indianapolis, Indiana.”

Image Description: “August 28, 1949 – Joseph Clovese, G.A.R. Veteran, 105 Years Old At The 83rd And Final G.A.R. Encampment In Indianapolis, Indiana.”