Figure 1: “Contraband, Changing Quarters” In this image, a determined-looking slave exercises his agency and escapes from his master in the Confederate army to seek freedom with the Union army. Presumably, the fine white stallion belongs to his master; so the Union has gotten two properties for the price of one. The cap, I guess, is a fashion statement.

Image Source: The Philadelphia Print Shop, section on Civil War images of Blacks / “Contraband”

First and foremost, you must understand this: Civil War era northerners were intrigued, perhaps even fascinated, by the very idea of “contrabands”: human property that was “confiscated” from Confederates, and given asylum from bondage, in return for supporting the Union war effort. That intrigue and fascination played out in the art of the era, as shown in this post.

Some background is in order. The official Union policy at the start of the war was to do nothing to slavery where it stood. The goal of the Union was to end secession, not to end slavery. Men like Abraham Lincoln were uncompromising that slavery not spread into the territories west of the Mississippi River, but they believed that free persons in the slave states had the right to keep chattel property.

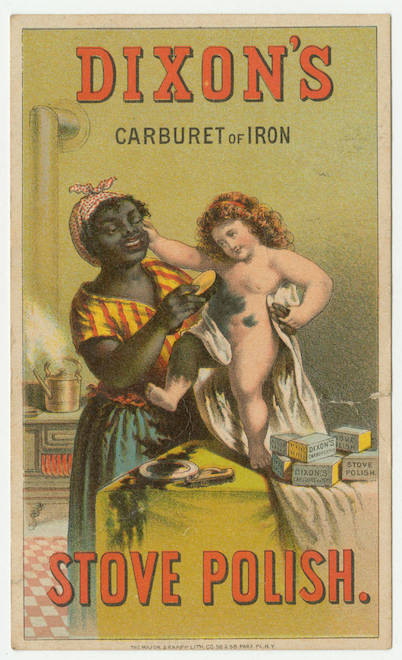

Figure 2: An enslaved person caricature with an impish grin says “I’se de INNOCENT CAUSE Ob All Dis War Trouble”

Image Description: This Civil War era envelope image shows an African American enslaved person slyly casting himself as the “innocent cause of all this war trouble.” Many African Americans no doubt agreed with this, but most likely, this reflects the sentiment of the illustrator and many white northerners. But the exigencies of war would transform the Negro from a mere trickster into a freedom seeker that the Union would embrace as “contraband.”

Image Source: Indiana State Library, Civil War Envelope Exhibit

Enslaved people had a different idea. They immediately saw the conflict between Union and Confederacy as an opportunity for freedom. In March 1861 – several weeks before the attack on Fort Sumter ignited the Civil War – two groups of slaves fled bondage and sought refuge at Fort Pickens, a Union occupied ports in northwest Florida. Their hopes for freedom were dashed. First Lieutenant A. J. Slemmer, a commander at the fort, reported to his superiors that “(o)n the morning of the 12th… four negroes (runaways) came to the fort entertaining the idea that we were placed here to protect them and grant them their freedom. I did what I could to teach them the contrary. In the afternoon I took them to Pensacola and delivered them to the city marshal to be returned to their owners. That same night four more made their appearance. They were also turned over to the authorities next morning.”

But just two months later, another group of runaway slaves got a different reception. On May 23, 1861, Frank Baker, James Townsend and Sheppard Mallory fled bondage and sought asylum at a Union occupied fort outside of Hampton, Virginia, named Fort Monroe. Per Union policy, the fort’s commander, General Benjamin Franklin Butler, should have returned them to their master. But he reasoned that because the slaves were property that was used by Confederate insurrectionists, it was within his rights to confiscate that property and use it for the Union’s purposes. This was the beginning of the Union’s contraband policy. The Lincoln administration, and then legislation passed by the Congress and signed by Lincoln, gave official sanction to the contraband policy. Soon, all across the Confederate States, the Union was enabling the freedom of former slaves.

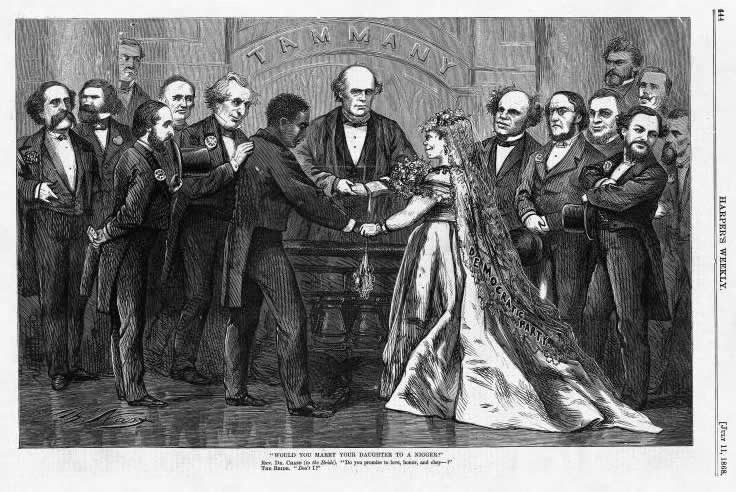

Figure 3: The Fort Monroe Three: Runaway slaves Frank Baker, James Townsend and Sheppard Mallory meet with Union General Benjamin Butler at Fort Monroe, Virginia, May 1861, seeking freedom from bondage. Butler will decide that this “contraband property” should be confiscated from the Confederates, and re-purposed for Union use.

Image Source: From The New York Public Library Digital Collections

This new policy created a sensation among northerners. Recollect that less than 2% of people living in the free states were of African descent. Millions of northern white Americans went their entire lives without ever seeing a real live African-American, much less a slave. What they did know of slaves was through a popular culture that commonly depicted slaves in a negative way, by, for example, using caricatures that exaggerated and “animalized” their appearance.

What were northerners thinking and feeling about this contraband policy? They might have thought about their Yankee ingenuity, in making what Southerners thought to be a strength – the unencumbered use of slave labor – into a weakness; and also, in finding a way to legally use enslaved peoples for the Union’s war aims. They might have thought about the irony, and the justice, of slaves gaining freedom just at the time when their masters needed them the most. Meanwhile, some northerners – such as Frederick Douglass – wondered why African Americans were called by a name that reinforced the idea of human beings as property.

Many white northerners no doubt wondered, just who were these people, anyway? Who were these people with dark skin, whom very few northerners had ever seen, but were at the crux of the divisions that caused the war, and were now being seen as being as a important to the Union’s success? They might also have wondered how the slaves felt about all of this… what did the slaves feel about their masters, the Union, and “freedom?”

And then there was the ultimate question: what did it mean for the Union to ask the support of, and give their support to, a class of people who were seen as ignorant, inferior, docile (when under control of their enslavers) yet savage (when uncontrolled), perhaps sub-human, but surely degraded?

These types of questions informed the popular art of the Civil War and post-war eras, the vast majority of which was produced by white men. Let’s take a look at some of those works:

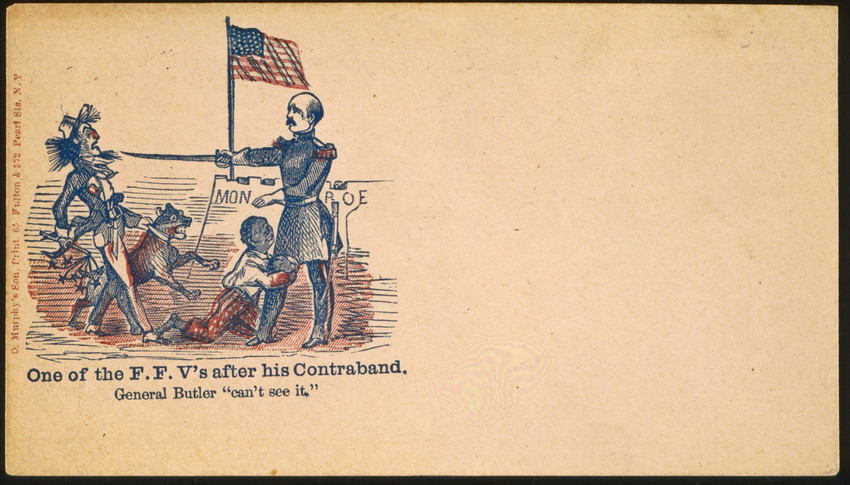

Figure 4: Front of a Civil War era envelope, titled “One of the F. F. V’s after his Contraband. General Butler “can’t see it.” Image Reference is to General Benjamin Butler; see text in the blog entry. F.F.V is short for ‘First Families of Virginia,’ a name given to the state’s elite class

Image Source: Encyclopedia Virginia; entry titled “Escaped Slaves at Fort Monroe”; image courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society

During the Civil War era, illustrated envelopes were a kind of social media. People used the mails to send printed envelopes which had artistic, political, or social content. During 1861 and 1862 – that is, after the contraband policy started, but before the final Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863 – several printers made envelopes which addressed the “contraband” Issue.

The image above portrays a Virginia enslaver, bloodhound in hand, going after his runaway. The groveling bondsman is protected at the point of a sword by Union General Benjamin Butler. Butler, as mentioned above, originated the contraband policy at Fort Monroe. The image is based on an actual event: a Confederate officer, under flag of truce, met with Butler at the fort to retrieve a runaway slave. Butler responded that the slave would be returned, if the Confederate officer would take an oath of loyalty to the Union. Which, of course, the officer did not do.

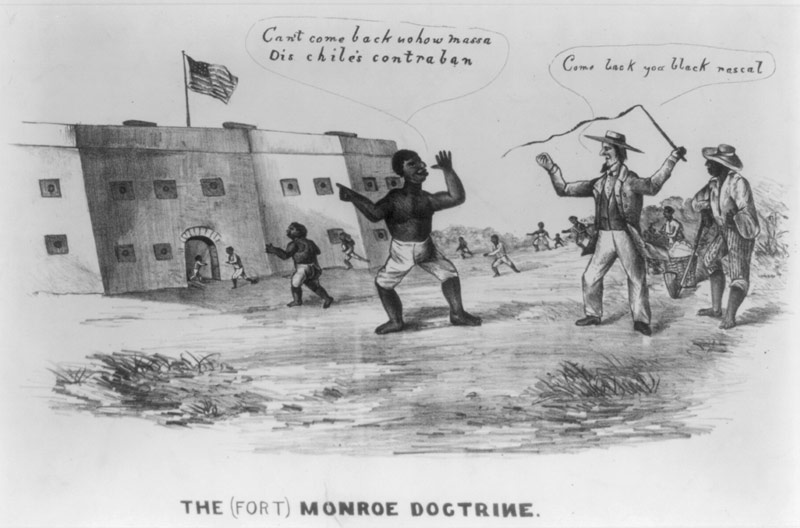

Figure 5: The (Fort) Monroe Doctrine, 1861. From the Library of Congress description: On May 27, 1861, Benjamin Butler, commander of the Union army in Virginia and North Carolina, decreed that slaves who fled to Union lines were legitimate “contraband of war,” and were not subject to return to their Confederate owners. The declaration precipitated scores of escapes to Union lines around Fortress Monroe, Butler’s headquarters in Virginia. In this crudely drawn caricature, a slave stands before the Union fort taunting his plantation master. The planter (right) waves his whip and cries, “Come back you black rascal.” The slave replies, “Can’t come back nohow massa Dis chile’s contraban”

Image Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog, Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-36161; above image is from the Virginia Memory website. Continue reading